An analysis of board games: Part I - Introduction and general trends

This is part I in my series on analysing BoardGameGeek data. Other parts can be found here:

- Part I: Introduction and general trends

- Part II: Complexity bias in BGG

- Part III: Mapping the board game landscape

Introduction

Over the last few years, board games have become one of my favoured pastimes. My journey of discovery in this space has been very enjoyable, but the deeper I delve down the rabbit hole, the more it makes me wonder about the board game landscape as a whole, particularly about the genres I haven’t tried, the different types of mechanics I’ve not been exposed to, games that have an unusual pairing of mechanics and how the board game landscape as a whole has evolved over time. I found a few different bits of analysis on Kaggle, in forums and blogs that scratched the surface of these topics, but not enough to relieve the itch of my curiosity, so I decided to get my hands dirty and rummage through the data mine myself.

Data collection and description.

BoardGameGeek is a fantastic database for board game information, so it seemed like a no-brainer to me to use this as the main source of the data for my analysis. There are pre-scraped and ready to use BGG datasets on Kaggle and GitHub, but neither of those suited my purpose since the Kaggle dataset is limited to the top 5000 board games on BGG and the GitHub dataset is 2 years old and is also missing some data fields that I was interested in such as a list of mechanics for each board game. I decided to re-run a modified version of the scraper I found on GitHub to allow me to fetch additional fields such as a list of mechanics, categories and designers that were not collected by the original scraper and obtain a slightly richer and more up-to-date board games dataset. This generated a dataset containing 76,597 board games and 13,675 board game expansions. The modified scraper and the scraped dataset can both be found here

For the analysis in this post, we’ll be focusing on base board games only, not expansions.

A note on sampling bias in the dataset

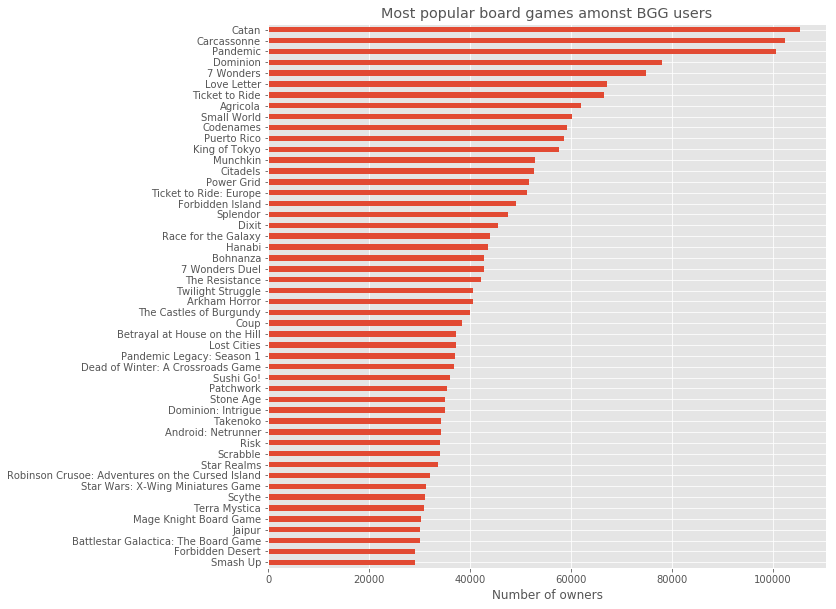

Before we delve into any any serious analysis, we should highlight that any patterns or observations found here reflect patterns observed within the boardgamegeek dataset. Depending on the context in the analysis, these observations may or may not be reflective of the board game industry as a whole, since the perspective and behaviour of boardgamegeek users will not always accurately represent all board game players. People who have a boardgamegeek account and actively log plays and rate games are very likely to be more invested and informed on board games compared to the average board game player. A good demonstration of this bias can be seen in the list of most owned games on boardgamegeek.

Whilst the exact sales figures are hard to come by, it is generally agreed that the most popular (by ownership, not rating) board games include Chess, Monopoly, Risk, Scrabble, Pictionary, Cluedo, Trivial Pursuit, etc. (sources: 1, 2, 3, 4). All of these games are under-represented in the BGG dataset due to the aforementioned bias. There will be many other cases in the analysis where this bias is likely having an effect, but I’ll address them as they come.

A golden age of board games

There has been a lot of discussion suggesting that we are currently in a board game golden age (sources: 1, 2, 3). I thought it would be interesting to see if the data supports this view.

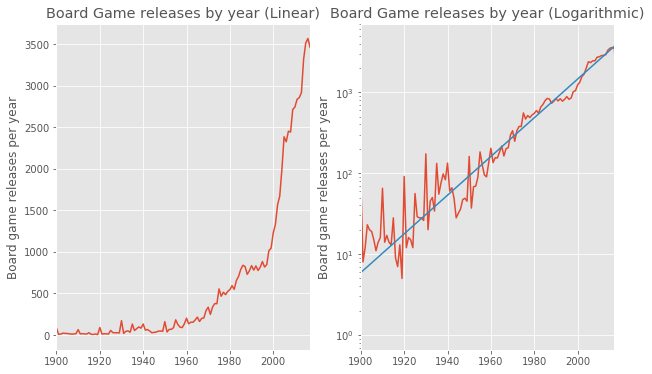

Board game publication rate over time

- Historically, there has been a broadly exponential increase in board games coming out each year.

- Based on the exponential growth of board game publications observed so far, we expect the number of board games published over the course of a year to double every 12.6 years. This is the board games analogue of Moore’s law

- We are currently observing the release of around

3,500new board games every year, and that number is increasing by around5.7%each year. - The growth of the industry appears to have stagnated between the mid 1980s and late 1990s. There was, however, a disproportionate surge in growth of number of board games released per year from 1999 to 2005 that made up for the stagnation observed in the previous years. It’s not entirely clear to me why the stagnation or surge occurred during those years, but given that the transition between the stagnation and surge aligns with the release of the boardgamegeek website (first available in 2000), it’s possible that these changes in new games published per year are an artefact in the data due to the availability of boardgamegeek (i.e. obscure board games before the existence of boardgamegeek may have been lost to the sands of time, whereas after the existence of boardgamegeek, it’s more likely that obscure games will still make it to the database).

- It is worth remembering that this is just referring to new games, and it doesn’t even include expansions!

- Overall, whilst the number of new board games released per year currently appears to be very high, it is currently in near perfect alignment with what’s expected given the historic growth trends of the board game industry. There is nothing particularly unique or different about the rate of release of new board games to support the view that we’re currently in a board game golden age. However, the rate of release of board games is just one of many aspects that could lead people to believe that we’re in a board game golden age. We can have a look at some other factors too.

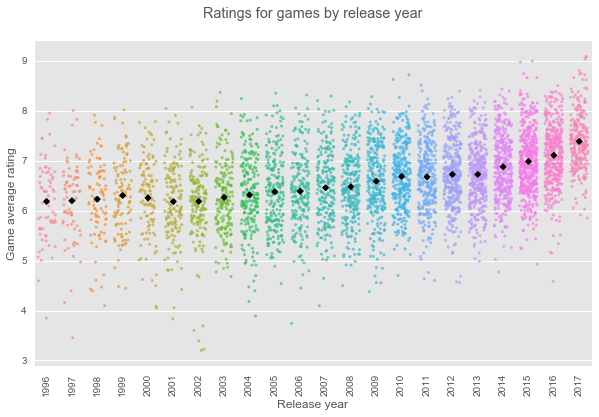

Board game ratings by publication year

This data suggests that board games have been getting steadily better since around 2002, but that there’s been a disproportionate improvement in in game ratings in the last couple of years. While the last couple of years certainly appears to have seen the release of great games such as Pandemic Legacy, Gloomhaven, Scythe, etc., it’s not clear to me what caused the games to get disproportionately better in the last couple of years. Perhaps the consumer market for board games increased in size noticeably, leading to more resources poured into game development, but unfortunately, I don’t have the data to test this.

It’s also worth noting that there may be an element of ratings inflation present in this data i.e. the baseline rating for an average game has increased, because people might have perceived a rating of 5 to be average a decade ago, but now they might perceive a rating of 7 to be average, so average ratings could be increasing over time despite games not necessarily getting better.

Other industry trends over time

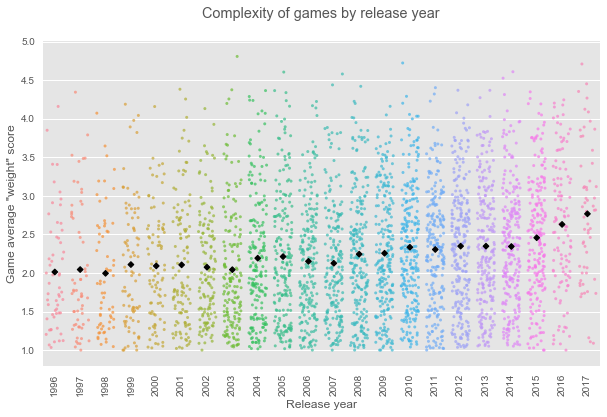

Complexity

The “complexity” of a board game is a relatively loosely defined term, since it encompasses different types of learning and decision making characteristics involved in learning how to play as well as playing a game. To give a quick example, Chess/Go are relatively simple games in terms of their rules. In both cases, the rules can all be concisely explained and understood in a few minutes. However, getting a full grasp of all the strategies and tactics made possible by these simple rules can take a very long time as there is a considerable amount of complexity born from the number of different moves possible each turn as well as the fact that every move affects the available possible moves in future turns (i.e. turns are not independent). Boardgamegeek contains a “weight” score board games (rated by users) that provides a reduced, all-encompassing sense of the complexity of a game, based on users’ perception. We can look at how the complexity scores of board games have evolved based on when games were released. I’ve focussed on games post 1995 since the dataset of games that have enough weight ratings before then starts to get a bit thin before then.

It appears that board games have not only been getting better in terms of ratings, but also more complex since the mid 1990s. The trends in the complexity mirror the trends we see in overall ratings, with games appearing to have gotten steadily more complex since the early 2000s, and the last couple of years exhibiting a disproportionate growth in complexity.

The parallels between the trends in overall ratings and complexity beg for a more direct comparison between them, but that’s a fairly substantial topic in itself, so I’ll address that in a future post of this series where the analysis has more room to breathe.

Mechanics

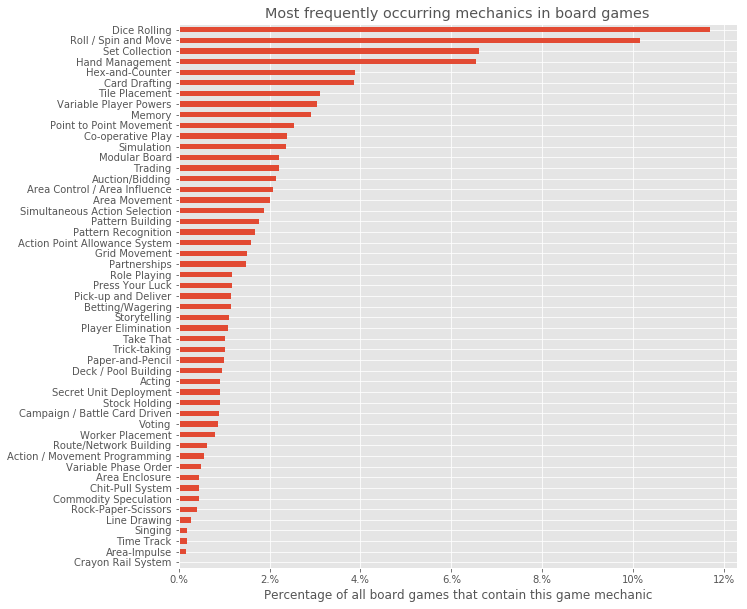

Mechanics are the basic constructs of rules or methods that allow you to interact with a board game to allow gameplay. These can be simple things such as dice rolling or drawing (e.g. Pictionary), to slightly more involved cases such as Card drafting or Route/Network building. I’ve listed the mechanics on BGG below by how often they’re found on board games. Many of the mechanics’ names are intuitive, but some require more explanation. Descriptions and examples of all mechanics can be found here

Most popular mechanics

Unsurprisingly, the top 2 are related to dice, which is often seen as an iconic staple of board games.

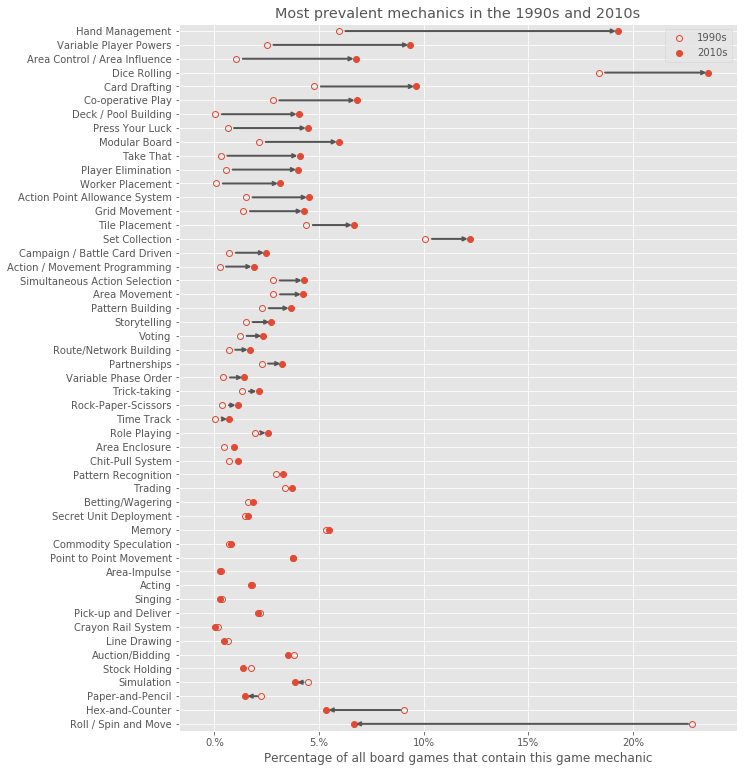

We can also look at how mechanics prevalence has changed over the last couple of decades.

There are several mechanics that have become more popular over the last couple of decades, but the most notable is Hand management (choosing which set of cards to keep in your hand and which to play/discard since some card combinations will be better than others and there may a limit on the number of cards you can keep in your hand. Examples of popular board games with the Hand management mechanic are Settlers of Catan and Pandemic). I don’t have any robust insight into why this might be the case, but it’s perhaps because it can incorporate interesting decision making elements into games without requiring much explanation or complicated rules. Once the function of the cards/sets of cards in your hand are understood, the intricacies of the trade-offs, risks and benefits of playing/discarding particular cards and managing your hand often become self evident. The theme of mechanics that force you to think and make decisions is also present in other mechanics on the rise such as Variable player powers, Area control/Area influence, Card drafting, Deck building, Worker placement, etc. On the other end of the spectrum, we have Roll/Spin and move mechanic (This is the mechanic present in Monopoly or Snakes and ladders in which the movement of a player’s token is decided by dice roll or the spin of a wheel) experiencing a huge decline. It’s perhaps unsurprising to see its decline since this mechanic requires little to no consideration or decision making at all, and is therefore a less engaging way to interact with a board game.

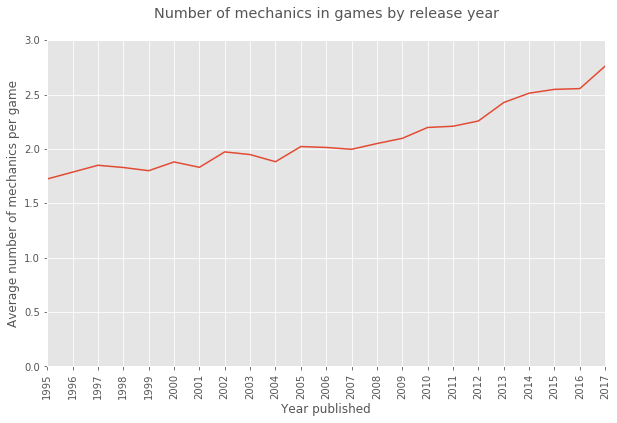

It is also worth noting that there are many more mechanics on the rise than on the fall. This is because modern games are beginning to include more mechanics. The inclusion of more mechanics over time is consistent with the analysis earlier suggesting that games are becoming more complex with time.

Themes

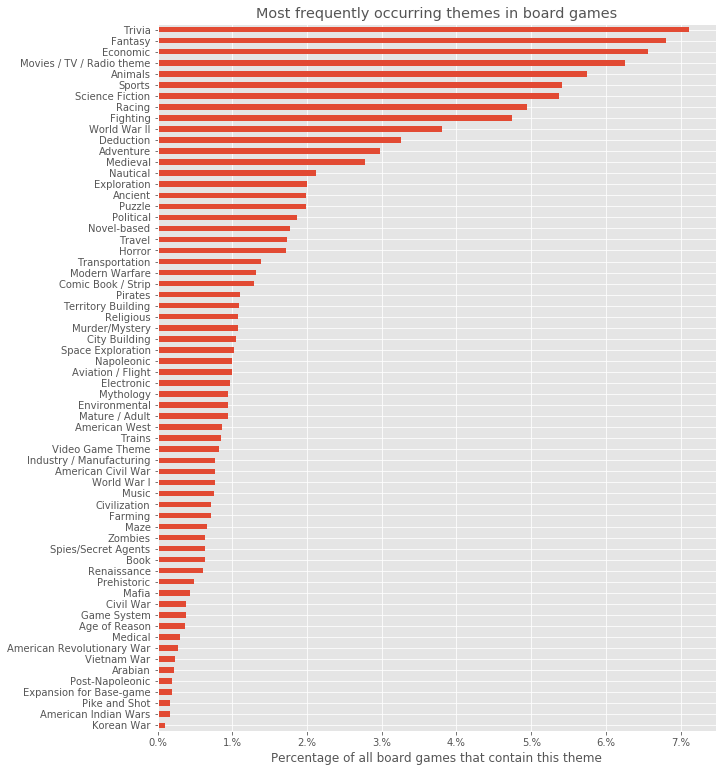

The BGG classification taxonomy for games is a little odd. At the highest level, they contain a game Type classification (e.g. Strategy, Thematic, Wargame, Party, etc.). There aren’t very many classification types, and more than 75% of games on BGG don’t even contain a Type classification, so I won’t be analysing it in this post, but if you’re interested in looking of most prevalent game types, etc. they can be found in the raw analysis Jupyter notebook file. The next level in the taxonomy is Category. A cursory look at the values in this field will show that it’s a disorganised mix of themes, game “types” and mechanics (as an example, Codenames contains the Categories: Party Game, Card Game, Word Game, Deduction, Spies/Secret Agents). I’ve manually filtered the list of tags in the Category classification level down to only include themes, since they were the elements that appeared most consistently under the Category classification. BGG also contains further levels of classification taxonomy, but I’ll only be looking into themes derived from tags in the Type field for this analysis.

The most popular themes in BGG are:

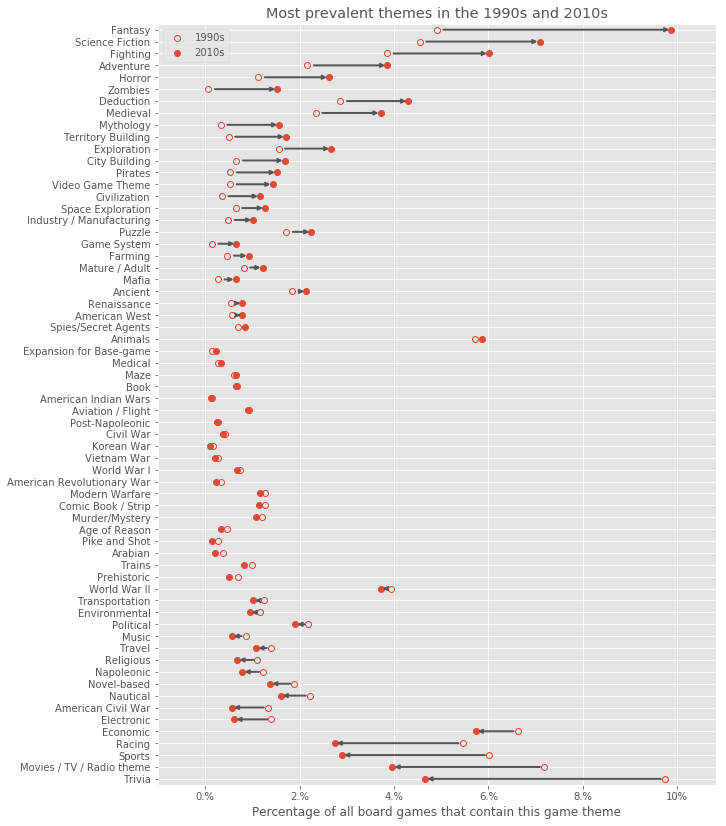

Similar to the mechanics, we can also see which themes have become more/less popular over the last couple of decades.

Looking at the most popular themes, there is a big shift occurring in the dominant themes present in games. In fact, 8 out of the top 10 most popular themes are either in the top 5 most rapidly rising or top 5 most rapidly declining lists, suggesting a strong and clear shift in the themes that engage the current generation of board game players. The themes that are on the rise include Fantasy, Science fiction and Fighting, whereas Trivia, Movies / TV / Radio theme, Sports, Racing and Economic are all on the decline. This seems to suggest that the themes that capture our imagination today are slightly less grounded in reality (at least compared to 20 years ago).

More analysis on the BGG dataset can be found in part II (Coming soon) of this series of analysis posts, in which we explore the relationship between mechanics, themes and game ratings.

I’ve left a lot of smaller bits of analysis that didn’t fit into the structure of this write-up, but if you’re interested in learning more about the board game dataset, you can find all of my analysis, including the code here in the form of a Jupyter Notebook (Python).

Thanks to:

- Colm Seeley for introducing me to the world of modern board games, countless discussions and ideas on interesting things to do with the dataset, helping me structure the analysis and for providing some manually collected data. I look forward to co-presenting this analysis with him in the future.

- Catherine Maddox for great feedback on the writing and presentation of the post

- Yihui Fan and Hugh Thompson for helpful feedback on the clarity and aesthetics of the graphs.

- GitHub user

TheWeathermanfor creating the BGG scraper that I modified for this analysis.

If you enjoyed reading this, you may also enjoy:

- Boardgamegeek dataset on Kaggle, with multiple users’ analysis on the datasets

- Are Boardgames Getting Better? An Empirical Analysis by Opinionated Gamers

- By the Numbers - BGG Rank Data + Analysis by Oliver Kiley